It started with an idea jotted down on a napkin at a bar in the Houston Heights in 2014, but the Program in Politics, Law and Social Thought (PLST) at Rice University has evolved into the most popular minor offered in the School of Humanities.

“Politics, Law and Social Thought is one of the crown jewels of a Rice undergraduate education,” says Dean of Humanities Kathleen Canning. “It allows students to combine history, theory and philosophy of law and political thought, taught by our most talented teachers in humanities, with courses in the sociological and political dimensions of law offered by social sciences.”

In its inception, the program aimed to fill a gap first identified by Harold Hyman, history professor, author and award-winning scholar of American legal history, and Katharine Drew ’44 ’45, the esteemed Rice history chair, former acting dean of humanities and social sciences and the first woman hired as a tenure-track faculty member by the university. The pair had once led a similar initiative at Rice, and Hyman’s daughter, U.S. District Court Judge and Rice trustee emeriti Lee Rosenthal, was the driving force behind its revival.

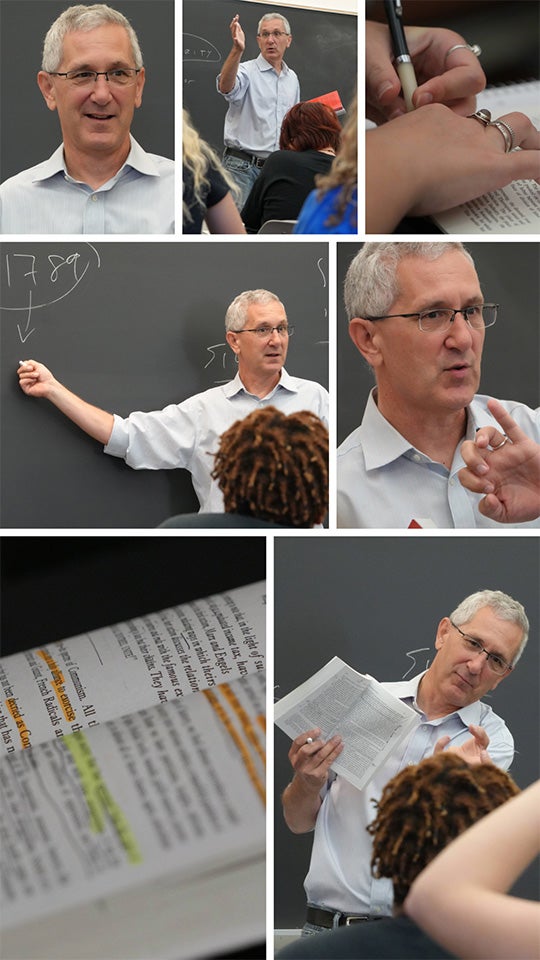

“She basically posed this question to me: Why don’t you have some kind of program that deals with big ideas and politics, the kind of stuff you work on, but also legal material?” said Carl Caldwell, director of PLST and the Samuel G. McCann Professor of History.

“Carl and I realized that we have the same kinds of students over and over again: students who were interested in history of political thought, students who were interested in law school and students who were intellectually driven by questions about the foundations of democracy,” said Christian Emden, the Frances Moody Newman Chair and professor of German studies.

Emden and Caldwell’s shared vision laid the foundation for the program’s creation. They initially envisioned PLST as a niche program for about 15 students who were passionate about engaging in deep discussions on political theory and law.

“We utterly failed,” Caldwell said with a laugh. “We have 95 students now.”

Ten years on, the program’s appeal lies in its interdisciplinary nature. While rooted in political theory, it attracts students from every school at Rice, bringing them together across disciplines to engage with the most pressing political and legal questions of the day.

“Who does specifically social and political thought?” Caldwell said. “Philosophy does a little, history does a little, political science does a little, sociology does a little. It’s not in one place.”

PLST is not just for students with an eye on law school, though its offerings have proven valuable for those on that path.

“We’re finding that the students with whom we work closely, who are in the speculative classes about thought, they’re getting into really top law schools,” Caldwell said, listing institutions like Harvard University, Stanford University and New York University among the schools where PLST alumni have been admitted.

One of the program’s standout features is its unique judicial practicum opportunities, which allow students to shadow appellate judges in federal or state courts. It was spearheaded by Judge Rosenthal in the federal court and former Houston First Court of Appeals Justice Evelyn Keyes, who implemented the program among her colleagues in the state court.

“I don’t know of any other program in the country that allows 15 or so of our undergraduates to shadow these top judges,” said Caldwell, who added that a parallel legal practicum offers internships with nongovernmental organizations and law offices.

The practicums are what first got the attention of senior history major McKenzie Jameson, who’s pursuing a PLST minor.

“During my time at Rice, though, I have really fallen in love with the program because of its emphasis on the study of both ideas and their applications,” Jameson said. “In Dr. Caldwell’s course on authoritarian constitutions, we spent the first six weeks of the semester focused solely on concepts such as populism, liberalism, democratic backsliding and autocracy, examining what these concepts mean and how they function on an abstract level. We then dedicated the second half of the semester to researching and investigating how these concepts play out in practice in diverse regions around the world.”

In that way, PLST pushes beyond prelaw preparation.

“The program is not about finding policy solutions,” Emden said. “We’re asking the truly foundational questions.”

One of Emden’s courses, Modern Political Thought, exemplifies this approach by engaging students with canonical texts that continue to resonate with today’s political landscape.

“They begin to realize that an author writing in the 17th century actually speaks to foundational political issues that we’re still facing today,” Emden said.

This realization, he added, is often eye-opening for students who discover that these historical texts offer new perspectives on modern debates about government, constitutions and democracy.

“I came to Rice as a student who was primarily passionate about studying American political and legal history, but the courses offered through PLST really encouraged me to expand my focus, ultimately stimulating a new interest in comparative law,” Jameson said. “Perhaps in contrast to prelaw programs at other universities, the PLST program really sits at the intersection of a variety of disciplines, which I believe leads students to develop the capacity to view problems and ideas through a more nuanced lens.”

That intellectual flexibility curated by a PLST minor has proven to be one of its most valuable assets in the professional world. Rather than preparing students for a singular career path, the minor fosters intellectual agility, allowing graduates to adapt to various roles across industries. The program’s emphasis on communication, critical reasoning and deep analysis also positions its students as highly desirable candidates in today’s dynamic job market.

“Students aren’t trained in this program; it’s more of an education,” Emden said, noting that the skills gained in the humanities and social sciences are precisely what make PLST graduates stand out. “Large corporations are looking for those kinds of people to hire for their senior positions.”

For students like Kayla Peden, a Rice senior majoring in political science and minoring in PLST, the program has provided insights into her future career path. Peden, who plans to attend law school, said that the courses offered by PLST have deepened her understanding of law and politics in a way that few other programs could.

“I saw that Rice offered the Intro to Law class with Professor Rudy Ramirez before I even applied to Rice, and that really got me interested,” Peden said. “It’s supposed to mimic your first year of law school, so you can see if that’s something that you’re actually interested in and something that you are capable of doing. I did and I loved it.”

Jameson highlighted associate history professor Aysha Pollnitz’s courses, such as Political Thought from Cicero to Locke, as “cult classics.”

“Within the small-group setting of the class, Dr. Pollnitz allowed each day’s discussion to be shaped by the questions we brought to class after having read the primary sources for the week,” Jameson said. “In this way, her course provided me with an opportunity to take an active role in my own learning and to engage directly with the interests and perspectives of my peers.”

As the program continues to grow, Caldwell and Emden are faced with questions about its future. With an ever-increasing number of students and expanding prelaw interest, Caldwell said PLST has reached a crossroads.

“We have too many students to continue simply being a minor with a smattering of courses here and there,” he said.

One possible next step is transforming the program into an enhanced minor and maybe eventually a major, which would allow for a more structured curriculum and expanded legal studies.

“We should never become merely a prelaw program,” Caldwell said, “but we could dramatically expand it into some kind of major that balances humanistic inquiry with legal education.”

Emden, too, said he sees potential for growth, including the possibility of establishing a center for democracy and ethics at Rice. Such a center, he believes, would position the university as a leader in addressing the foundational questions about democracy, justice and political thought with which PLST grapples.

“We’re not a local university; we’re a global university,” Emden said. “Adding a center would provide Rice with another dimension of reaching out beyond the hedges and showing how extremely relevant our work really is.”